The question of Medicare sustainability is in tandem with Social Security sustainability. Both...

The most common concern I hear from people is regarding the federal debt and its impact on the economy, and in turn their portfolios. I wanted to discuss some facts about the U.S. federal debt as well as some “facts”, which are just fiction.

It is true that on a gross level that the debt is at an all-time high. I think it is imperative though to look past the first level when speaking of the debt issue. First, the key number is the federal debt owned by the public. This backs out what is called intragovernmental debt. Per the U.S. Treasury, as of 10/21/2019, debt owned by the public was $16.9 trillion while intragovernmental debt was $6 trillion, for a total of $22.9 trillion. Intragovernmental debt is debt the U.S. owes itself. You really can’t owe yourself money. Let’s say you have 2 savings account. One is your new auto fund, which actually has more money in it than you need to buy the car you want, and the other is your fund to buy that special present you have picked out. You go to buy that present but realize you don’t have enough cash in your “present” fund. You borrow $250 from your “car” fund to buy the present. Do you really owe yourself since there is a surplus in the car fund? It is just an accounting game.

Next, debt in of itself doesn’t tell us much. If one couple has $1 million in debt and another has $250,000 in debt, would you assume the couple with $1M is worse off? What if the couple with $1M in debt has a net worth of $10 million, while the couple with $250 thousand only has $100 thousand in net worth? Your ability to repay the debt is more important than the debt number by itself. In this regard, debt as a percent of a country’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product, or think revenue) is key, not just absolute numbers. Per the Congressional Budget Office, federal public debt (excluding intragovernmental debt) as a percent of GDP hit over 112% in 1945. GDP for the U.S. was $5.3 trillion in the 2nd quarter 20191. Annualizing that and then just using the Federal Public Debt of $16.9 trillion give us approximately 79% debt to GDP. High, but nowhere near record highs.

Some might conclude that even 79% is too high. They are right in one regard but incorrect on another. Again, we must dig down another layer. Once again, debt, in of itself, is neither good nor bad. If a bank offered you a zero percent loan (no gimmicks), would you take it? Sure, even if you just put it in 2% interest bearing CDs you would be coming out ahead. Gross debt isn’t the most important metric, public debt isn’t either, nor is debt as a percent of GDP. The most important metric is the cost of debt. This really isn’t much different than buying a home at the consumer level. If interest rates are lower, you can afford more home or are able to pay less for the same home versus when rates are higher.

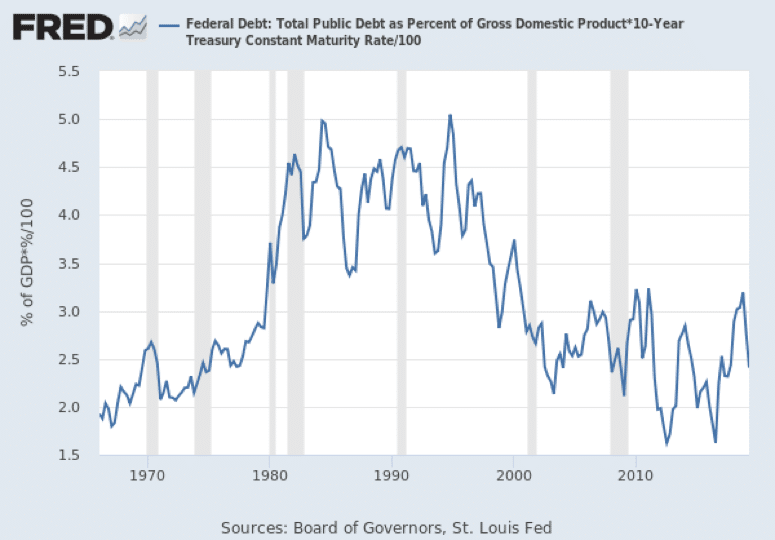

The actual cost of debt for the U.S., as a percent of GDP, is relatively low versus our historical norms. Basically, we can hold more debt today verses the 1980s or even 1990s due to interest rates being much lower. Back to the house metaphor, two factors play a part in how much you can borrow; your salary (or GDP for a country) and interest rates. The U.S. revenues (GDP) are higher and interest rates are lower than those decades. As the chart below shows, the cost of debt is less than the 1980s and 1990s:

The World Bank found that public debt levels of greater than 76% of GDP leads to a slowing economy2. Whether we officially cross that number in 2019 or 2020, it is safe to say we could rather soon. It is important to note that crossing that threshold doesn’t mean a recession or worse, it just means it will impact the economy negatively when levels reach over 76%.

But it isn’t as simple as this statistic may seem because it depends not just on debt levels, but interest rates also. The real key is the ability of the U.S. to carry the debt from a cost perspective. As long as interest rates stay low, and the true cost of the debt as a percent of GDP doesn’t rise much, the debt levels are sustainable.

This is why I believe we will see low interest rates for much longer than many expect. I predicted in 2009 that we could see the U.S. follow the Japanese economy of the 1980s and see low interest rates for over 2 decades. I still believe that is a possibility.

Which gets me to one concern that many have that isn’t a concern of mine and that is China dumping all the U.S. treasuries and causing U.S. interest rates to rise fast. That would be the very definition of cutting off one’s nose to spite their face. It would crash the Chinese economy, since they are much bigger exporters to us than vice versa. Not only would it kill their economy, where are they going to move all that money? Germany with their negative interest rates? Japan’s 10-year government bond is negative also. You can get 1.32% in Greece. Do you really want to hold trillions of Greece paper? The U.S. is the safest place for countries to hold debt and also still pays a positive interest rate, even if it is very low.

Finally, we all know we can only kick this can down the road so far. There are long-term concerns such as what happens if/when China is successful in becoming a self-efficient economy that doesn’t need exports to grow? What if inflation takes off and interest rates do rise significantly down the road?

Bottom line, don’t let it scare you today in how you invest. Any negative economic impacts about the debt is years away. However, let’s not throw this completely at the younger generation’s feet and say “you take care of it.”

Sources:

The information provided here is for general information only and should not be considered an individualized recommendation or personalized investment advice. The economic forecasts set forth in this material may not develop as predicted.